COVID-19 and Immigration

A Boundless report uses public data to understand how the coronavirus pandemic has impacted U.S. immigration

COVID-19 & Its Impact on Immigration

The COVID-19 pandemic has significantly stemmed the flow of immigrants to the United States, with the processing of immigrant visas — both within the country and abroad — coming to a near standstill in 2020. Entry into the United States along the Mexican and Canadian borders — including by asylum seekers and unaccompanied children — has been severely restricted. Immigration enforcement actions within the U.S. were reduced, although not stopped entirely, at the height of the pandemic in 2020, but enforcement ramped up again in 2021.

Tens of thousands of people remain in immigration detention despite the high risk of COVID-19 transmission in crowded jails, prisons, and detention centers that U.S. Immigration and Customs Enforcement (ICE) uses to hold noncitizens. The pandemic led to the suspension of many immigration court hearings and limited the functioning of the few courts which remained open or were reopened. Meanwhile, millions of immigrants and their families were left out of legislative relief from Congress, leaving many people struggling to stay afloat in a time of economic uncertainty.

While most of 2020 was spent trying to understand the novel virus and how it spread, 2021 was focused on development and distribution of a safe and effective vaccine for COVID-19, as well as on removing barriers to immigration caused by the pandemic and the former administration’s enforcement priorities.

Source: American Immigration Council, The Impact of COVID-19 on Noncitizens and Across the U.S. Immigration System

COVID-19 Timeline

Source: American Journal of Managed Care (AJMC), A Timeline of COVID-19 Developments in 2020 and A Timeline of COVID -19 Vaccine Developments in 2021; American Immigration Council, The Impact of COVID-19 on Noncitizens and Across the U.S. Immigration System; American University Investigative Reporting Workshop (IRW), Timeline: Biden’ s Immigration Policy.

Impact on Immigration Services

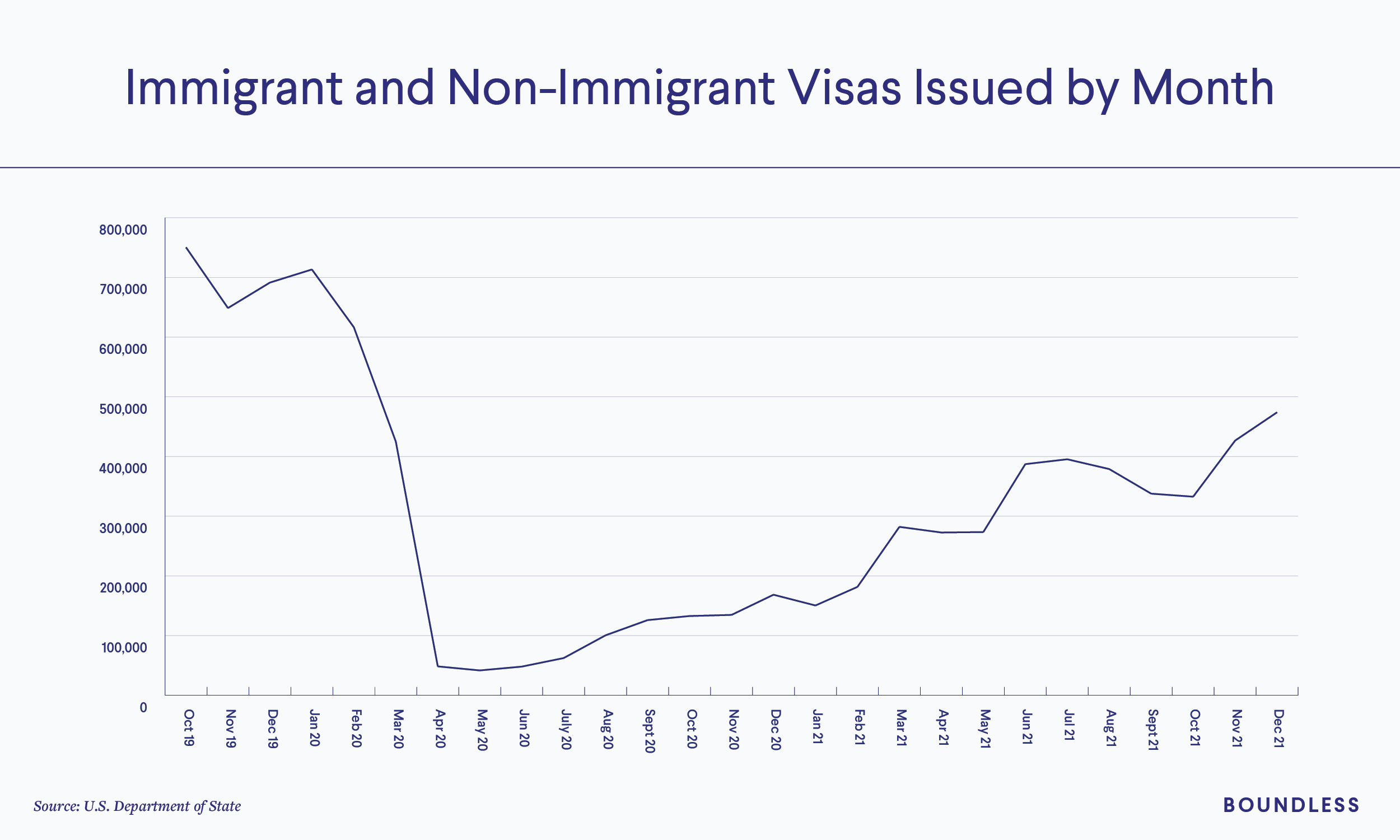

Although the rate of issuance of visas has increased dramatically since the historical lows of April/May 2020, as of December 2021 visa issuances have not yet rebounded to the levels seen in late 2019.

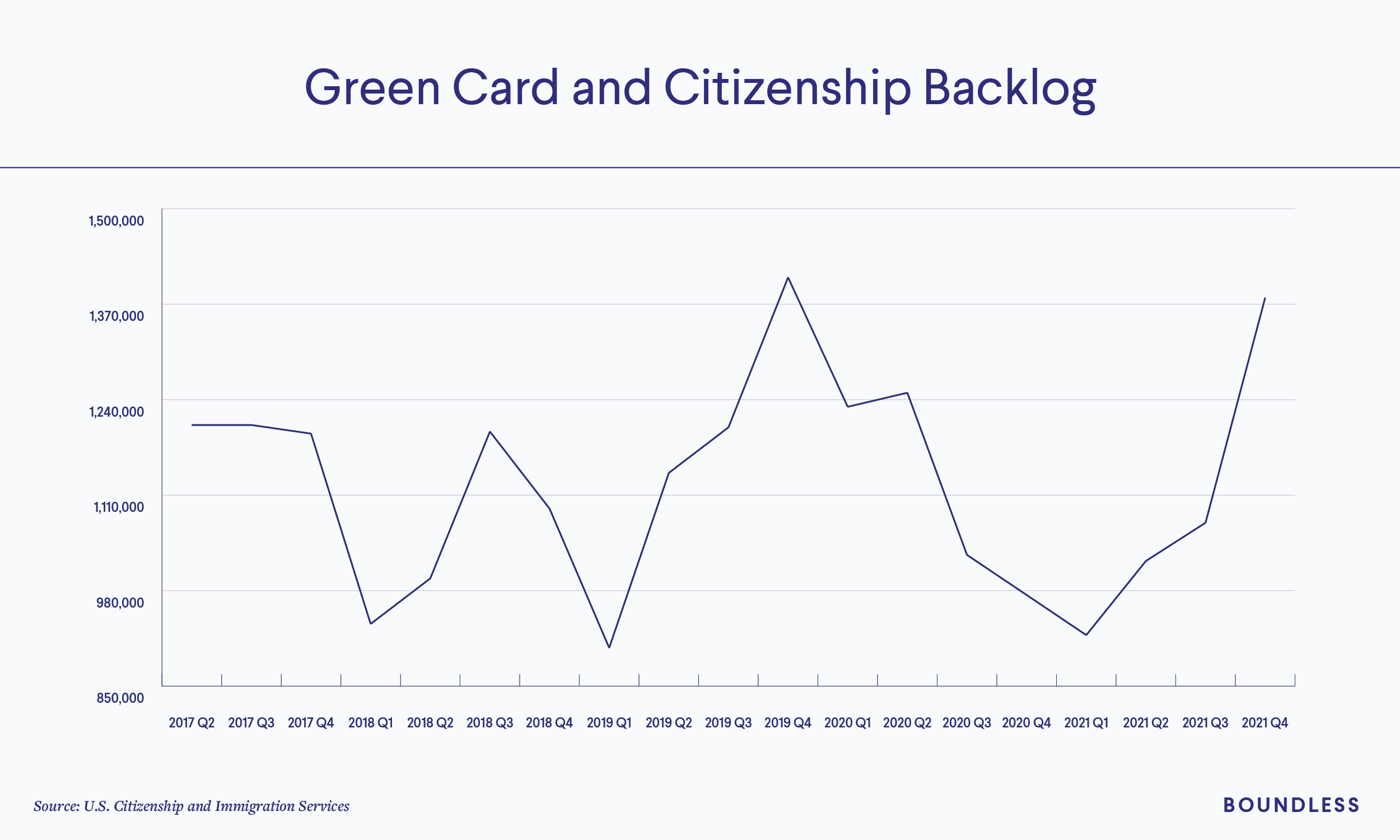

According to the Department of State, the slowdown in visa processing generated much fewer visa entries and a large backlog of more than 460,000 people with unprocessed visas as of late 2021.

Source: Migration Policy Institute, Immigrants’ U.S. Labor Market Disadvantage in the COVID-19 Economy: The Role of Geography and Industries of Employment

Disproportionate Impact on the Foreign-Born Labor Market

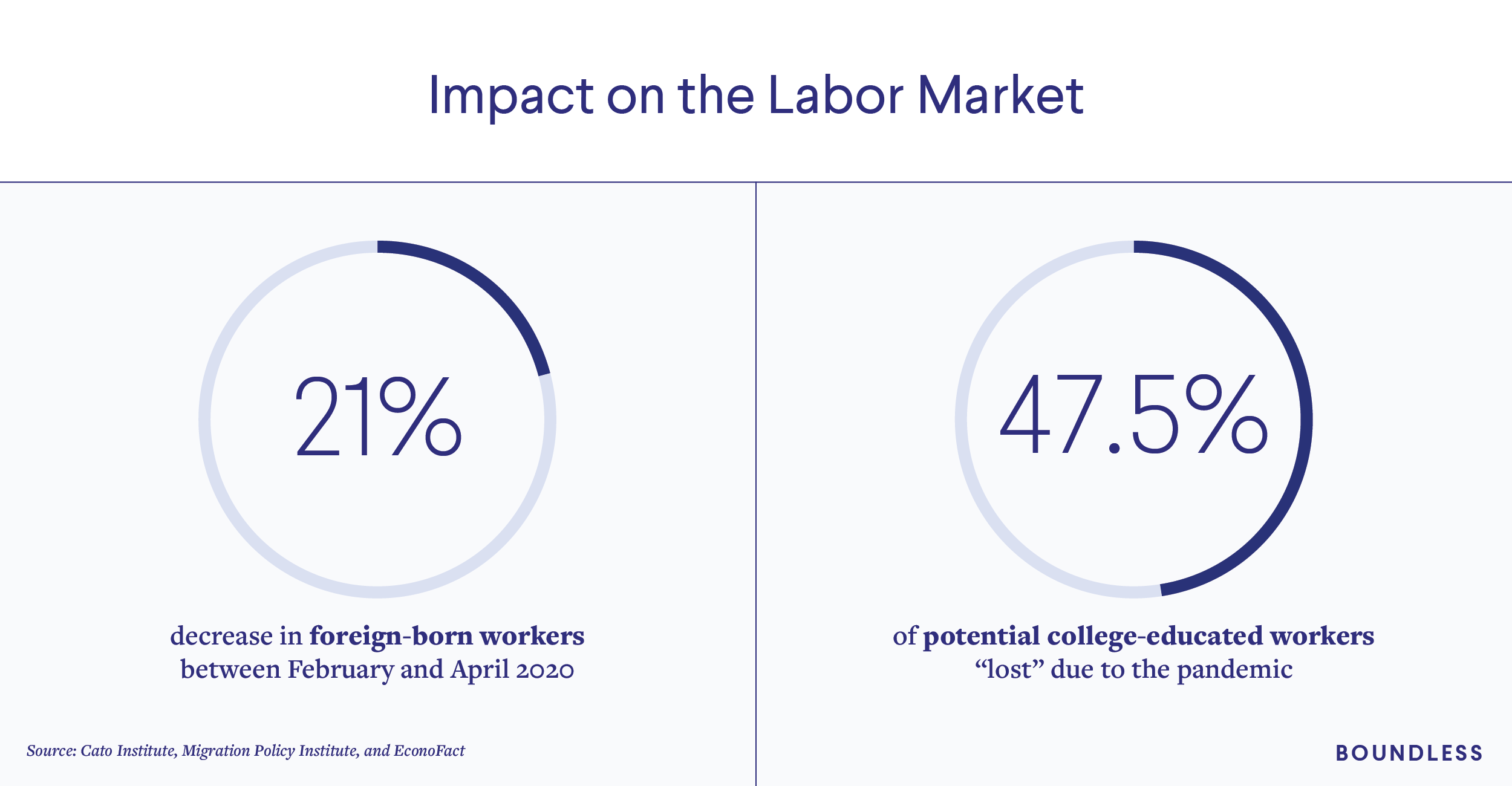

The U.S. government has issued about 1.2 million fewer visas to adult immigrants, refugees, and temporary foreign workers abroad since consulates were closed in March 2020 (through July 2021) compared to the period from March 2018 to July 2019 before the pandemic. The decline in immigrant and nonimmigrant visa arrivals (45% and 54%, respectively, from October 1st 2019 to September 30th 2020) resulted in zero growth in working-age foreign-born people in the United States. In contrast, the foreign born population of working age (18 to 65) grew by about 660,000 people per year prior to 2019.

The Bureau of Labor Statistics (BLS) has reported more than 10 million job openings from June to August 2021, which was more than double the historical average. Those sectors that had a higher percentage of foreign workers in 2019 had significantly higher rates of unfilled jobs in 2021; it is estimated that an industry that had a 10% higher dependence on foreign workers than another industry in 2019 saw a 3% higher rate of unfilled jobs in 2021.

Although the U.S.-born working-age population grew by 2.6 million, the total number of working-age immigrants (ages 16 and older) fell by 0.7 percent, or about 313,000 individuals between March 2020 and July 2021. By the end of 2021 there were about 2 million fewer working-age immigrants living in the United States than there would have been if the pre-2020 immigration trend had continued unchanged. A calculation done using Current Population Survey (CPS) monthly data has indicated that of the missing 2 million foreign-born workers, about 950,000 would have been college-educated had the pre-pandemic trend continued. This substantial loss of skilled workers is equal to 1.8 percent of all college-educated individuals working in the US in 2019.

Source: Cato Institute, U.S. Issued 1.2 Million Fewer Visas to Work‐ Eligible Foreigners Since March 2020; Migration Policy Institute, The ‘Trump Effect’ on Legal Immigration Levels: More Perception than Reality?; EconoFact, Labor Shortages and the Immigration Shortfall

Disproportionate Economic Impacts of COVID-19 on Immigrant Communities

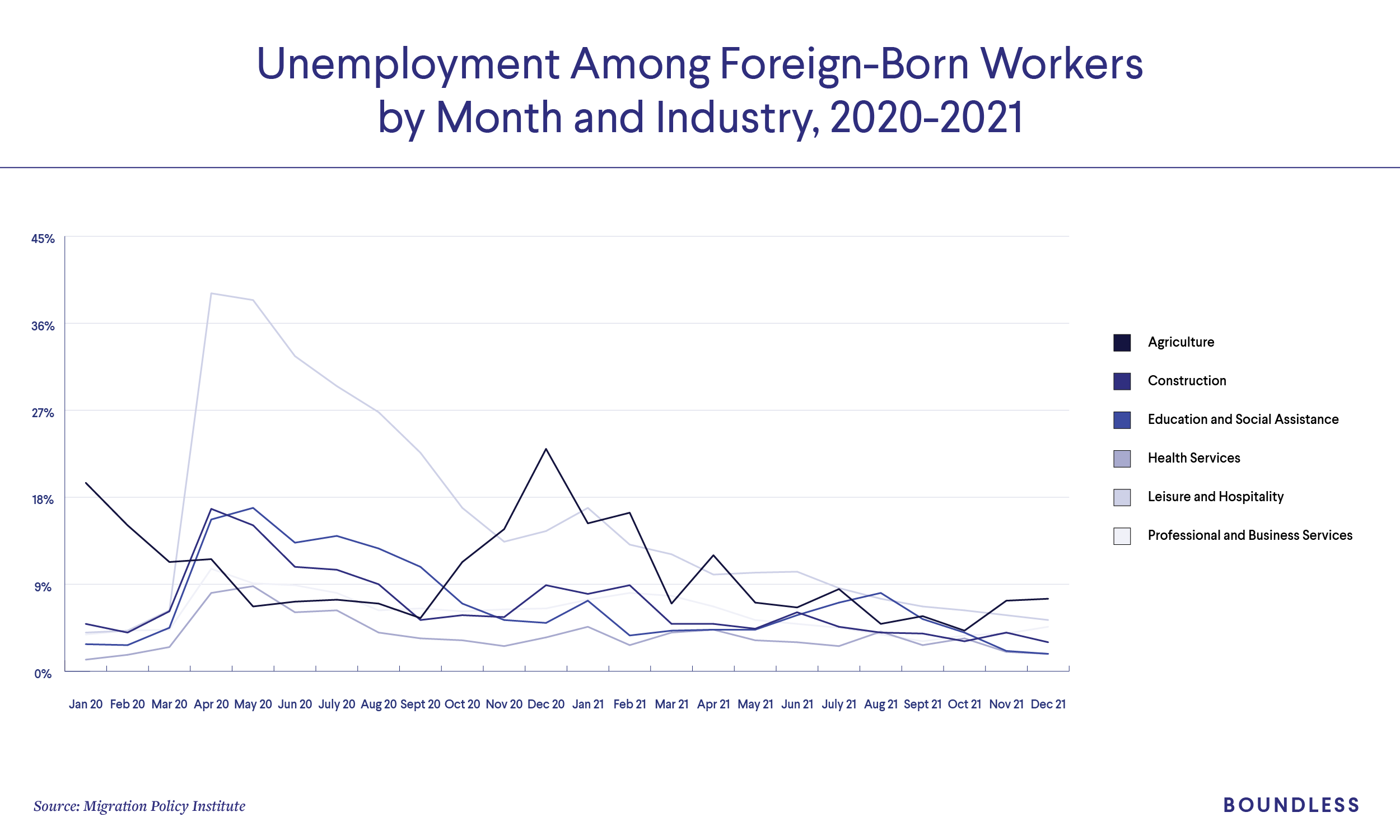

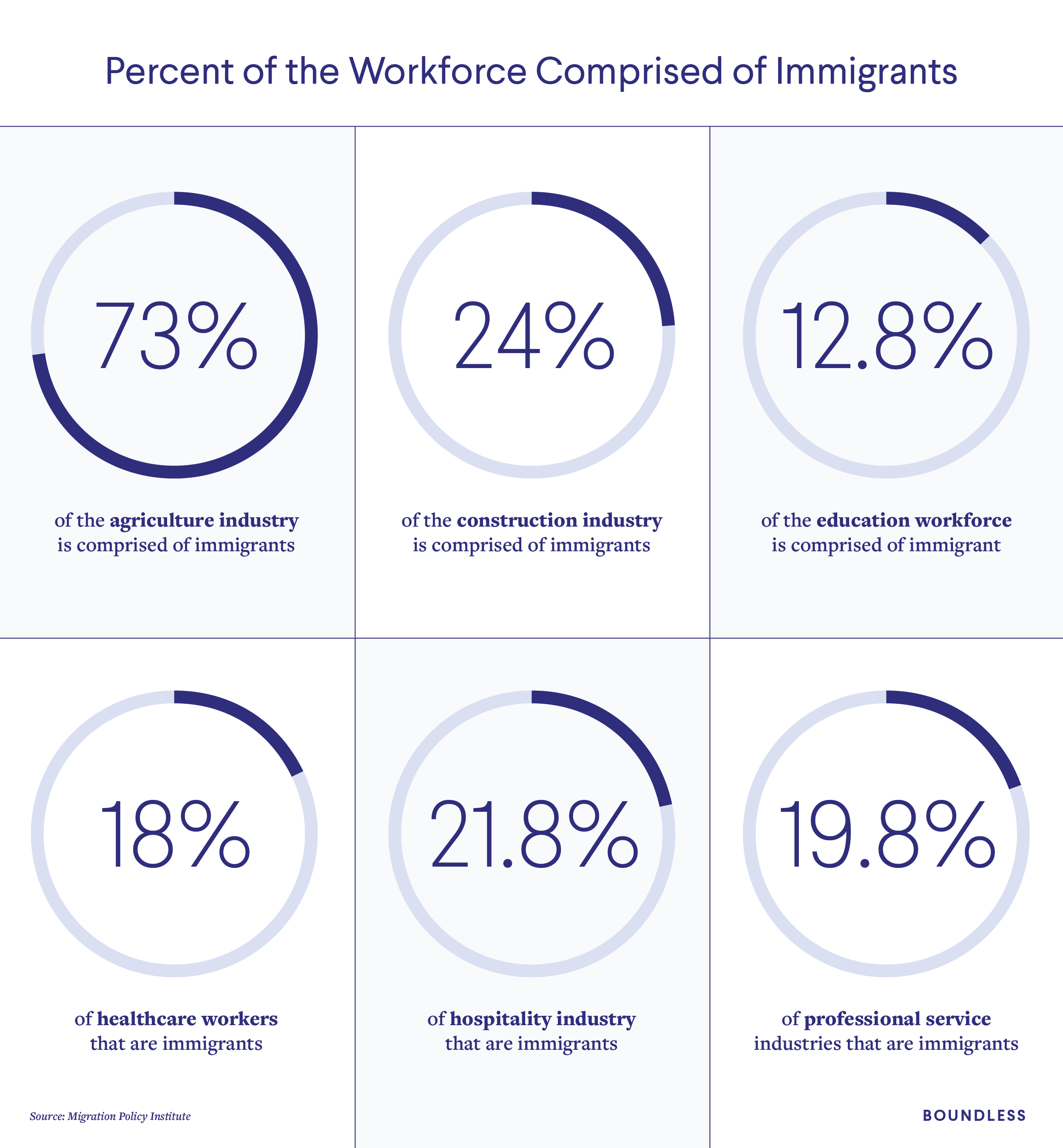

Unemployment rose dramatically in 2020 in the wake of COVID-19, the effects of which have been disproportionately felt by minority groups including Hispanic, Asian, and Black Americans. Immigrants may face particular hardship because they are more likely to work in affected occupations.

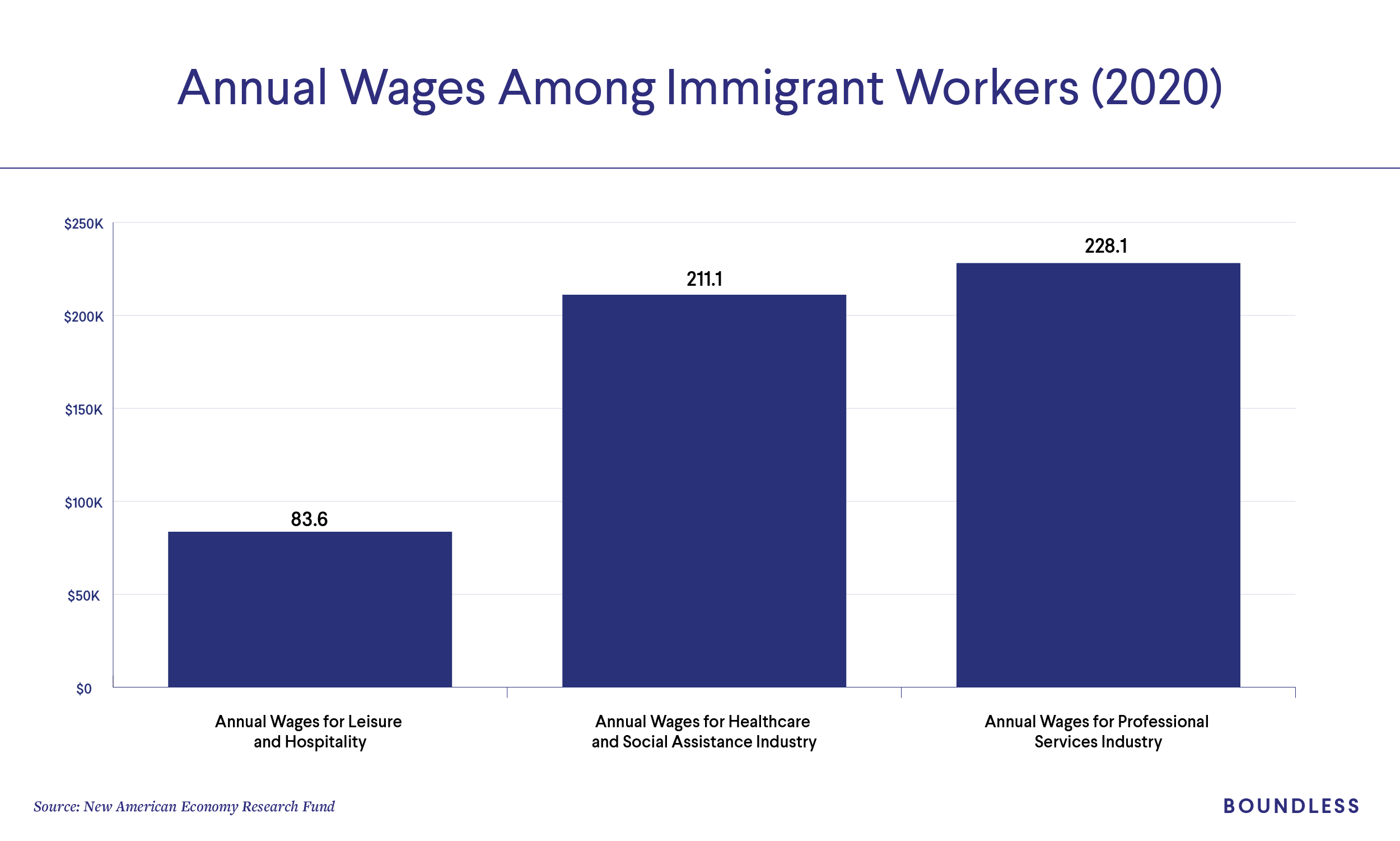

While the Covid-19 pandemic and resulting economic shutdowns have continued to disproportionately impact unemployment among foreign-born workers relative to U.S.-born workers, by July 2021 unemployment among the foreign-born had fallen below that of U.S.-born workers. Given their concentration in industries and regions of the country with still-elevated unemployment rates however, immigrants have remained at an economic disadvantage even as the country begins its post-pandemic recovery. Immigrant workers remain over-concentrated in major metropolitan areas on the coasts with high unemployment rates due to their reliance on tourism and on the demand for goods and services in central business districts by office workers—many of whom have yet to return to in-office work. Foreign-born workers also tend to be more concentrated in industries that require in-person services, such as leisure and hospitality, construction, and food services, in contrast to industries made up of a smaller share of foreign-born workers, such as education/social assistance services, professional and business services, and health services—which had relatively low unemployment rates.

Economic distress among non-citizen immigrants is of particular concern because, unlike immigrants who have become citizens through naturalization, non-citizen immigrants are frequently excluded from safety net programs, and many are ineligible for emergency benefits authorized by Congress.

Source: EconoFact, Coronavirus’ Disproportionate Economic Impacts on Immigrants; Migration Policy Institute, Immigrants’ U.S. Labor Market Disadvantage in the COVID-19 Economy: The Role of Geography and Industries of Employment

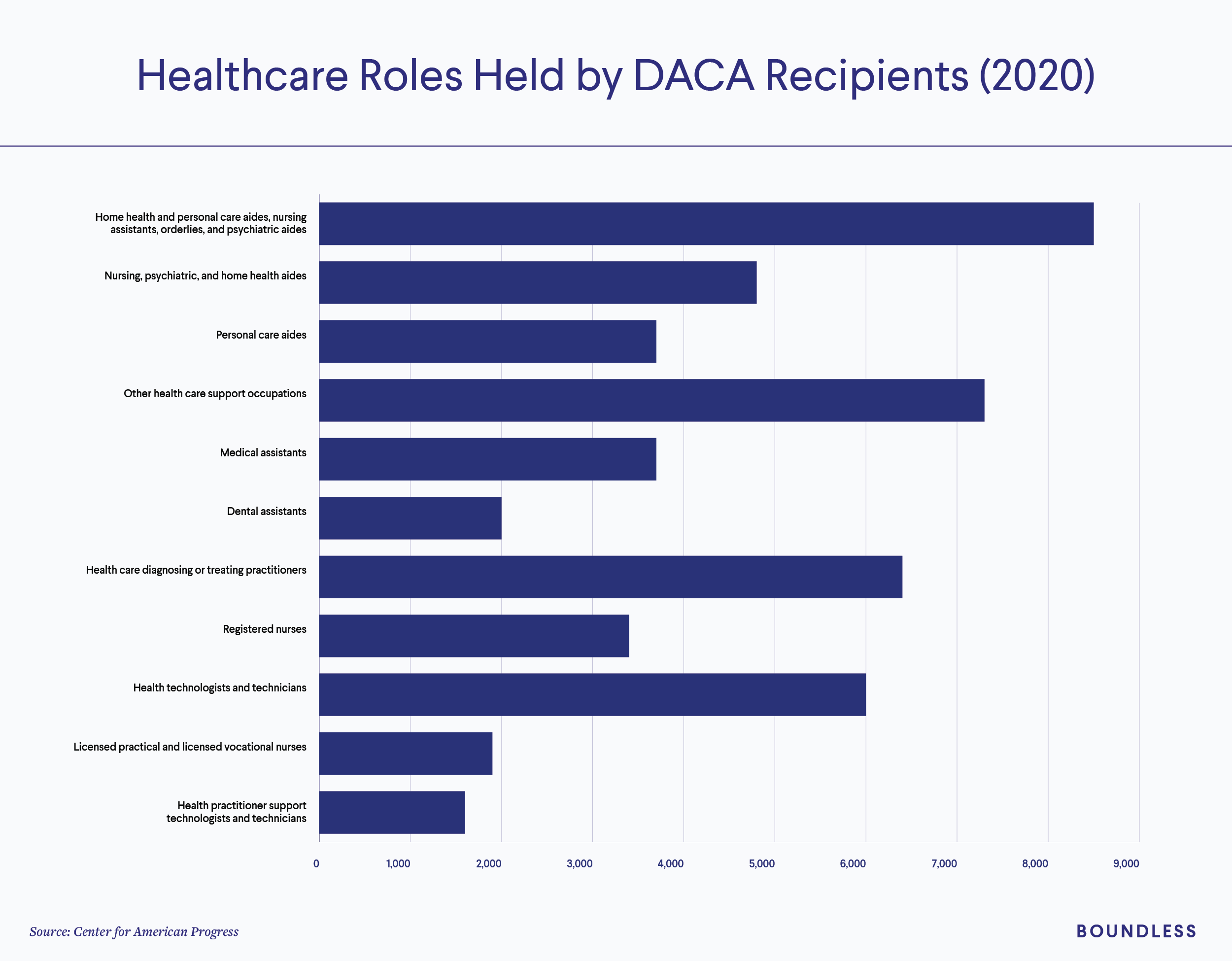

DACA Recipients on the Frontlines of the COVID-19 Response

According to the Cybersecurity & Infrastructure Security Agency (CISA), part of DHS, “essential workers” are those “needed to maintain the services and functions Americans depend on daily and that need to be able to operate resiliently during the COVID-19 pandemic response.”

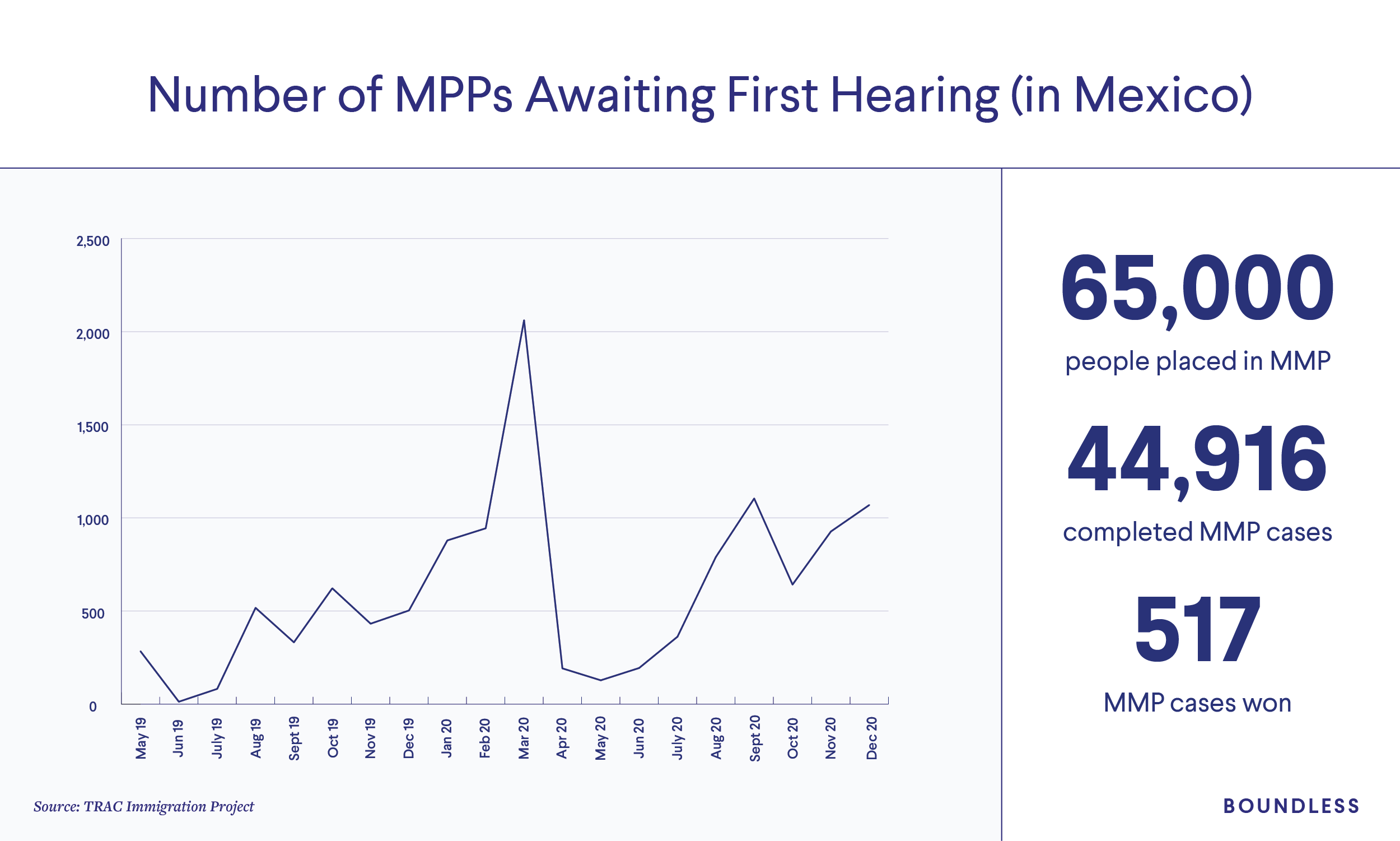

The Effect of COVID-19 on Immigration Processing at U.S. Land Borders

In January 2019, prior to the appearance of COVID-19, the U.S. government implemented Migrant Protection Protocols (MPP), whereby certain foreign individuals entering or seeking admission to the U.S. from Mexico – illegally or without proper documentation – can be returned to Mexico to wait outside of the U.S. for the duration of their immigration proceedings. Being outside of the U.S. makes it extremely difficult for asylum seekers to access attorneys and resources in support of their cases. As of March 2020, nearly 65,000 people had been put into MPP, with just 517 of them winning protection out of 44,916 completed cases.

On March 20, 2020, the United States reached joint agreements with the governments of Canada and Mexico to suspend “non-essential” travel through ports of entry on each border. On the same day, the Department of Health and Human Services (HHS) issued an emergency regulation which permitted the Director of the CDC to “prohibit … the introduction” of individuals when the Director believes that “there is serious danger of the introduction of [a communicable] disease into the United States.” Citing the new CDC authority under Title 42 of the U.S. Code, the Border Patrol began “expelling” individuals who arrived at the U.S.-Mexico border, without giving them the opportunity to seek asylum. By the end of August 2020, over 147,000 people had been “expelled” at the southern border. In addition, all MPP hearings at the border for asylum seekers sent to Mexico were suspended indefinitely awaiting the abatement of the pandemic, leaving more than 20,000 people stranded in Mexico or forced to abandon their cases and return home. In the two years since the invocation of Title 42, nearly 1.5 million people have been expelled from the U.S.-Mexico border, including at least 200,000 parents and children, and nearly 16,000 unaccompanied minor children.

Source: The American Immigration Council, The Impact of COVID-19 on Noncitizens and Across the U.S. Immigration System; Immigration Impact, Dueling Court Orders May Decide Fate of President Biden’s Title 42 Expulsions; The American Immigration Council, Rising Border Encounters in 2021: An Overview and Analysis

Increased Border Crossings

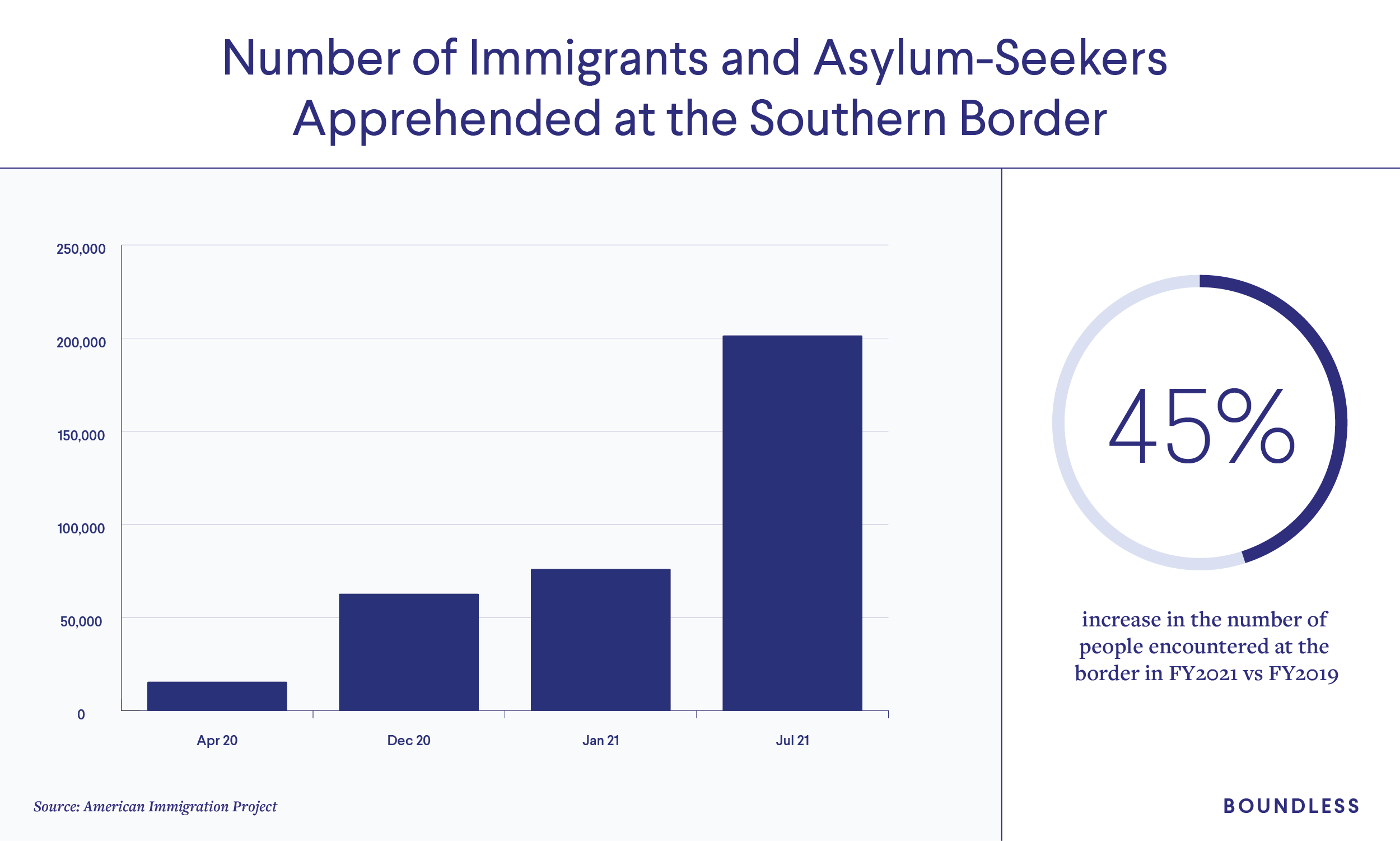

The Biden administration fully suspended new enrollments in MPP, however Title 42 was kept in place. Ironically, Title 42 has now increased border crossings, in large part by creating a situation where the majority of single adults are rapidly processed and sent right back to Mexico without a deportation order. Almost immediately after Covid-19 lockdowns were lifted across Mexico and Central America, the number of single adults seeking to enter the United States at the southern border began rising rapidly, from a low of 14,754 in April 2020 to 62,041 in December 2020. This was the highest number of apprehensions for a December in 15 years. The upward trend has continued, with the number of asylum seekers and migrants apprehended after crossing the border between ports of entry increasing from 75,316 in January 2021 to a high of 200,658 in July 2021.

This arrangement has incentivized repeated attempted crossings, however, and thereby created inflated estimates of the total number of people crossing the border. Despite nearly twice as many border apprehensions in FY 2021 than in FY 2019, the actual number of people encountered at the border was only 45% higher than in 2019.

Source: The American Immigration Council, Rising Border Encounters in 2021: An Overview and Analysis

About the Data

The following public sources were used:

- The American Immigration Council, The Impact of COVID-19 on Noncitizens and Across the U.S. Immigration System

- The American Journal of Managed Care (AJMC), A Timeline of COVID-19 Developments in 2020

- U.S. Citizenship and Immigration Services, Immigration and Citizenship Data, All USCIS Application and Petition Form Types (Fiscal Year 2020)

- TRAC Immigration Project, Details on MPP (Remain in Mexico) Deportation Proceedings

- U.S. Department of State, Visa Statistics

- The COVID Tracking Project, COVID Racial Data Tracker

- Department of Homeland Security, Cybersecurity & Infrastructure Security Agency (CISA)

- Immigration Impact, Dueling Court Orders May Decide Fate of President Biden’s Title 42 Expulsions

- Center for American Progress, A Demographic Profile of DACA Recipients on the Frontlines of the Coronavirus Response

- New American Economy Research Fund, Immigrant Workers in the Hardest-Hit Industries

- EconoFact, Coronavirus’ Disproportionate Economic Impacts on Immigrants

- Bureau of Labor Statistics, Unemployment rate rises to record high 14.7 percent in April 2020