These days, it seems like the federal government is announcing new immigration policies all the time. Yet often it’s difficult to tell the difference between what’s a real change and what’s still just in the planning stages.

That distinction — between an immediate impact and an unfinished proposal — makes a huge difference in people’s lives.

So what’s the difference? Understanding the answer requires a bit of background on the federal regulatory process. Bear with us — we’ll make this as non-boring as we can…

Regulation: It Ain’t Over Till It’s Over

When Congress makes a law, it’s called a statute. Everyone knows how that works (or at least the cartoon version).

But most lawmaking isn’t done by Congress — it’s delegated to the executive branch, where an alphabet soup of federal agencies hammers out the nitty-gritty details of the rules that govern our lives.

When a federal agency makes a law, it’s called a regulation. Very few people know how that works (and highly paid lawyers and lobbyists like it that way).

There’s a specific “rulemaking” process that federal agencies typically must follow in order to turn a policy idea into the law of the land. And until this entire process is finished, the status quo doesn’t change:

(1) Proposed rule: First, the agency publishes a formal proposal in the Federal Register (that’s the daily newsfeed of the executive branch, and also an outstanding cure for insomnia). Often described as a “proposal,” “draft,” or “plan,” this document is supposed to provide the legal and economic rationale for issuing a new regulation.

(2) Public comment period: For the next 30–90 days, the proposed rule is open for public comments. This means that anyone is allowed to send the federal agency their feedback — whether in support or opposition, and whether sending in a single sentence or a densely reasoned treatise.

(3) Internal deliberations: Next, the federal agency is obligated by law to read through all of the public comments, prepare a response to every serious argument, and consider changing course. This stage typically takes the longest (more on that below).

(4) Final rule: The agency publishes a “final” rule in the Federal Register, including a detailed justification for why it chose to either follow or ignore the comments it received from the public. After this extremely long and arcane FAQ, the final rule concludes with the actual text of the new regulation.

(5) Effective date: There’s usually a 30- to 90-day delay between the final rule publication and the “effective date,” giving the public some time to prepare for the new regulation.

Increasingly these days, there’s also an unofficial sixth step: The lawsuit. It’s possible to sue DHS in federal court and demand that a new regulation be blocked, but only once the final rule has been issued.

The Waiting Is the Hardest Part

When you read about a “draft” or “proposed” regulation, that means there’s a long way to go before anything actually changes.

How long? For immigration regulations, the answer is more than a year, on average.

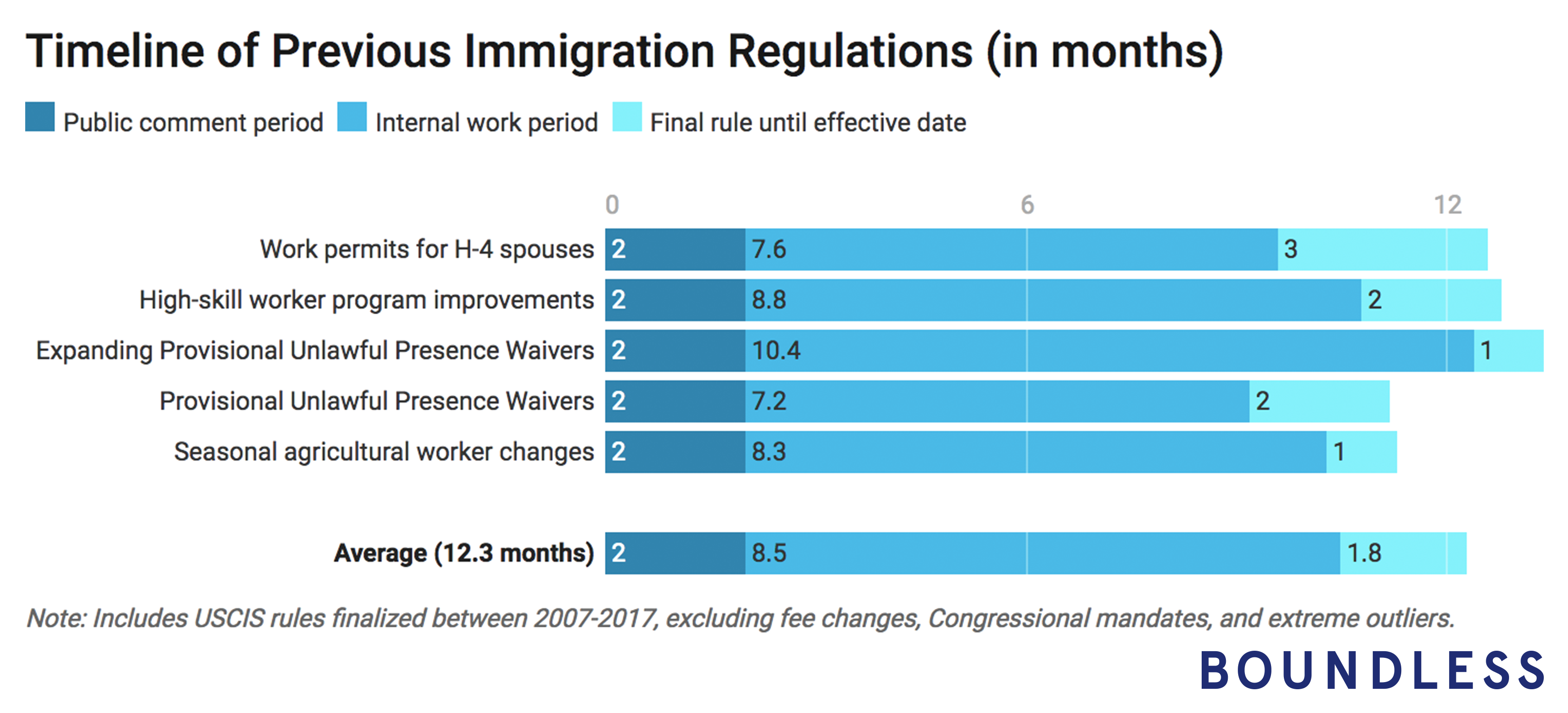

Boundless looked at every regulation from the U.S. Department of Homeland Security (DHS) that affected the legal immigration system over the past 15 years. (We excluded unusual cases, such as when DHS was in a big rush due to the looming end of an administration or a court-imposed deadline.)

That left us with 5 immigration regulations that reveal a pretty consistent pattern: 2 months of public comments, about 8.5 months of internal deliberation, and then about 2 months’ delay between final rule and effective date.

All in all, that’s an average of 12.3 months between the publication of a draft rule and the effective date of a final rule. In other words, the immigration announcements making headlines today may not go into effect for another year or more.

What’s Coming Next?

Over three years into the Trump administration, DHS and other agencies have finalized a few big immigration regulations. There is an ever-growing number of draft rules that DHS has published, and many more in the pipeline. Learn more here about what immigration measures could still be coming down the pike.

The administration is behind schedule on many of these regulations and will probably continue to fall behind.

That’s typical across administrations of both parties — the political leadership wants to move faster than the bureaucracy can handle.

When (and whether) any one of these regulations is actually enacted will depend on many factors, including:

- How many public comments does the agency have to respond to?

- How much internal disagreement is there — both within the agency and across the executive branch — during both the draft and final rule stages?

- How many other regulations are competing for the same people’s attention?

- Ultimately, does the government get sued?

That’s why it’s worthwhile to apply some skepticism whenever you see a headline that the administration has released “plans” or a “draft rule” to get something done. If it’s a regulatory plan, it could be well over a year before anything changes.

Wait, What About Executive Orders?

Right now you may be thinking, “If immigration policy takes so long to implement, then how does President Trump make so many changes seemingly overnight?”

The answer is that some policy changes — even dramatic ones — don’t go through the full regulatory process we just took pains to outline for you. For example:

The travel ban: Congress long ago granted unusually broad authority to the President to ban entire classes of people from entering the United States on national security grounds, just by issuing an executive order. That’s how it was possible (however controversial) to block some people from entering the United States while they were still in planes.

Asylum: The Trump administration acted to make it much harder for people crossing the U.S./Mexico border illegally to be granted asylum. This did require a new regulation, but the administration skipped to the last step using an “Interim Final Rule” — think of this as an emergency measure with no draft version and no public comments. This was an extraordinary move that was certain to be challenged in court.

DACA: When the Obama administration created the Deferred Action for Childhood Arrivals (DACA) program in 2012, it wasn’t through a regulation — instead, the Secretary of Homeland Security exercised her discretion to “defer action” (delay deportation) and provide work permits for undocumented Dreamers who’d been brought to the United States as children. When the Trump administration attempted to eliminate the program in 2017, it was through another DHS memo. Now the fate of the program is tied up in court, with one side arguing (among other things) that a full regulation was required to create DACA in the first place and the other side arguing that a full regulation was required to eliminate DACA.

Smaller things: It’s routine for DHS to issue “policy memoranda” to its immigration officers. Recent examples include new constraints on H-1B workers, expanded denials of visa applications, and more. As long as these policy memos are clarifying existing law and not creating new law, they can be implemented immediately without a full-blown regulation. But it’s increasingly common to see lawsuits attempting to block these policy memos, arguing that DHS should have gone through the full regulatory process.

Bottom line: Sometimes an immigration policy change can happen immediately. The devil is in the details, and the details may get snarled up in court.

Watch this post; we’ll keep it up to date! (Regulatory timelines were updated from a previous version posted on Nov. 9, 2018.)

Boundless is constantly monitoring changes to the U.S. immigration system. Stay informed by following Boundless on Twitter or Facebook.