From the earliest days of European colonialism to the present, tensions between so-called nativists and immigrants have been a recurring theme in American history. During colonial times and in the United States’ first decades, nativist sympathies focused on suspicions of Catholics, who often had connections to England and America’s sometime rivals France and Spain. U.S. Catholics’ ties to a global church hierarchy headed by the Pope stoked fears of foreign conspiracies to undermine the new republic. During the Jacksonian era, anti-Catholic newspapers flourished and native Protestant and Irish Catholic gangs squared off in American cities. In 1845 anti-Irish nativist riots shook Philadelphia.

The Irish Potato Famine, which began in 1847, spurred huge waves of immigration — over the next eight years 2.75 million immigrants came to the United States, largely from Ireland. The most influential nativist group of the era, the Know-Nothing Party, was formed in part out of fear of growing Catholic influence in the Democratic Party. The Know-Nothing Party (so named because their fear of conspiracy led members to habitually deny knowledge of their party’s workings) renamed itself the American Party and nominated former president Millard Fillmore in the 1856 Presidential Election (he lost to James Buchanan). The Know-Nothings’ influence faded during the Civil War.

During the second half of the 19th century, large numbers of immigrants from southern and eastern Europe came to the United States. The majority of these were Catholics or Jews, and few of them spoke English. This wave of immigration spurred a new nativist reaction championed by many Progressive politicians, who stoked fears that foreigners were taking the country from native-born Americans. During the era, relatively small numbers of Japanese and Chinese immigrants stoked nativist fears in the western U.S., spurring the 1882 Chinese Exclusion Act.

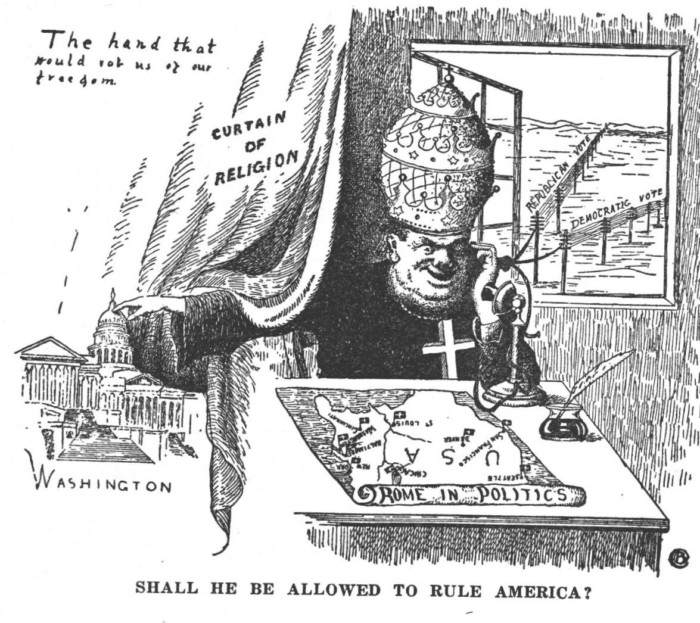

During World War I, anti-German sentiment flared in the U.S., spurring harassment of German immigrants and their descendants. After the war, the turmoil of the Russian Revolution led to “Red Scares” that targeted Eastern European immigrants — many of them U.S. citizens — whose leftist politics led them to be viewed as subversives. Meanwhile, anti-Catholic sentiment rose again with the founding, in 1915, of the modern Ku Klux Klan, which harassed Catholics, Jews, and immigrants as well as African Americans. In the American Southwest and California, anti-Mexican sentiment led to mass deportations in the 1920s and 1930s.

Nativist sentiment declined in the decades after World War II, in large part due to the longstanding effects of the Immigration Act of 1924, which had severely restricted immigration from non-northern-European countries: there were simply fewer immigrants to be alarmed about. The Immigration and Nationality Act of 1965 and a follow-up act in 1990 opened up U.S. immigration to people from all over the world again. In recent decades, nativist sentiment has risen again in some quarters, in part over concerns about the millions of undocumented immigrants, mostly from Mexico and Central America, who live and work in the U.S.

Not what you were looking for?

If you were expecting a textbook or academic study website, you may be looking for the former Boundless website. Boundless Immigration empowers families to navigate the immigration system more confidently, rapidly, and affordably with the help of our award-winning software and independent immigration lawyers.

Learn more about marriage green cards and U.S. citizenship in our immigration resource library.